3 juni, 2025

What is China’s message to the Global South?

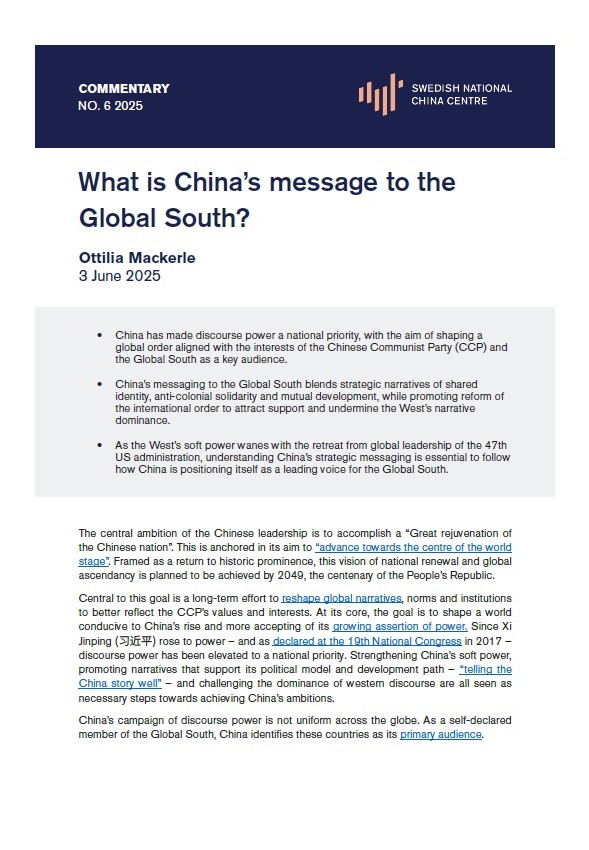

China's Foreign minister Wang Yi and Senegal's Foreign Minister Yassine Fall at Forum on China- Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), Beijing 2024 /AP/TT/ Ken Ishii

- China has made discourse power a national priority, with the aim of shaping a

global order aligned with the interests of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Global South as a key audience.

- China’s messaging to the Global South blends strategic narratives of shared

identity, anti-colonial solidarity and mutual development, while promoting reform of the international order to attract support and undermine the West’s narrative dominance. - As the West’s soft power wanes with the retreat from global leadership of the 47th US administration, understanding China’s strategic messaging is essential to follow how China is positioning itself as a leading voice for the Global South.

The central ambition of the Chinese leadership is to accomplish a “Great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. This is anchored in its aim to “advance towards the centre of the world stage”. Framed as a return to historic prominence, this vision of national renewal and global ascendancy is planned to be achieved by 2049, the centenary of the People’s Republic.

Central to this goal is a long-term effort to reshape global narratives, norms and institutions to better reflect the CCP’s values and interests. At its core, the goal is to shape a world conducive to China’s rise and more accepting of its growing assertion of power. Since Xi Jinping (习近平) rose to power – and as declared at the 19th National Congress in 2017 – discourse power has been elevated to a national priority. Strengthening China’s soft power, promoting narratives that support its political model and development path – “telling the China story well” – and challenging the dominance of western discourse are all seen as necessary steps towards achieving China’s ambitions.

China’s campaign of discourse power is not uniform across the globe. As a self-declared

member of the Global South, China identifies these countries as its primary audience. China’s messaging there rests on narratives of shared identity, history and aspiration. China has found both opportunity and necessity: an audience more receptive to its messaging, a group of countries crucial for institutional support in international forums and a space in which it can present itself as an alternative to the West.

To unpack the themes shaping China’s messaging to the Global South, this analysis looks at the official discourse on China’s flagship initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI) and the Global Security Initiative (GSI), alongside state media narratives and Xi Jinping’s speeches delivered in international forums such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and the G20.

Solidarity: “China is a natural member of the Global South”

China’s professed solidarity with developing countries is the foundation of China’s messaging to the Global South and the main strand of a narrative that claims shared experiences of colonialism with developing countries. China claims that it is not an outsider, but an integrated part of the Global South: “China will always be a natural member of the Global South...maintaining our roots in the Global South”.

The ideas of solidarity with the oppressed peoples of the world and decolonial unity are rooted in China’s historical alignment with anti-colonial movements and post-colonial states, and was first articulated to Asian and African leaders at the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia. At the time, premier Zhou Enlai (周恩来) reassured African and Asian leaders of China’s peaceful intentions, which was an important signal given lingering memories of China’s imperial past. Today, the legacy of both anti-colonial solidarity and the Bandung Conference is frequently invoked – often referred to as “Carrying forward the Bandung Spirit”.

While this messaging deliberately simplifies history – downplaying its own imperial past and current ethnic policies in Xinjiang and Tibet – it positions China as a companion on a shared journey and a partner rather than a dominant power. By reinforcing a narrative of South-South solidarity, China hopes to gain legitimacy and moral authority in advocating for a new global order more favourable to developing nations.

Mutual benefits from China’s engagement: “Win-win cooperation”

“Win-win cooperation”, a well-established part of China’s diplomatic vocabulary, has been institutionalised under Xi Jinping in initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative and the Global Development Initiative. It frames bilateral ties and economic cooperation with countries in the Global South as equal and mutually beneficial. It also serves to contrast China’s approach with that of western actors’ alleged “zero sum game” or “winner takes all” strategies, which are portrayed as unequal and conditional on adopting western political models. In this context, China’s model – focused on infrastructure, trade and industrial development – is framed as pragmatic, respectful and non-intrusive; for instance: “China-Africa cooperation is not about geopolitical calculations but about genuine win-win partnerships….We reject external interference and neo-colonial practices”.

Modernisation with Chinese characteristics: “Building a just world of common development”

The message to the Global South is simple: “If China can make it, other developing countries can make it too”. The Chinese development experience is presented as a model that prioritises economic development, industrialisation and technological advancement, but without the liberal political reforms typically associated with western development paradigms. Here, China positions itself as both a success story and the provider of an alternative route to modernity – one that affirms the right of developing nations to pursue development on their own terms as “modernization no longer means westernization”. China also emphasises development as the foundation of human rights, thereby shifting the conversation from political freedoms to economic well-being.

This narrative is also encapsulated in China’s Global Civilization Initiative, a diplomatic framework that promotes the “common values” of equality and respect for civilisational diversity, and describes modernisation as a path shaped by each country’s “national conditions” rather than a “copy and paste” approach. The GCI reinforces the idea that development can follow distinct, culturally rooted trajectories.

Reforming the global order: “True multilateralism”

A consistent theme in China’s outreach is the call for a more “just” and “inclusive” system of global governance, indicating that the current system disadvantages the Global South and, by extension, China as a natural member of this group. In its rejection of what China calls the “unipolar system”, which it perceives primarily as the United States only benefiting itself, China calls for “true multilateralism” in which all countries have an equal say in shaping global norms.

China’s call to reform the global order means reform of international institutions such as the United Nations, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to better represent developing nations, as well as leveraging international forums to create alternate venues for cooperation outside of western-dominated systems. However, when discussing multilateral ties, Xi Jinping often speaks of “dialogue without confrontation, partnership without alliance”. In this sense, China’s view of multilateralism arguably reflects a preference for flexible, bilateral arrangements over binding, rules-based agreements.

Peace, security and stability: China “opposes the pursuit of one’s own security at the cost of others’ security”

China positions itself as both a peaceful nation on the rise – as official discourse often puts it, “love for peace is in the DNA of the Chinese people” – and a constructive force in global peacebuilding, particularly in Africa. Here, it emphasises the principle of non-interference, positioning this in contrast to what it portrays as a western interventionism that is coercive, politicised and indifferent to national sovereignty. In Chinese messaging, ongoing conflicts in the Global South – especially in Africa – are often attributed to external, typically western interference and as closely linked to underdevelopment.

China’s ambitions for global security are formulated in the Global Security Initiative, which is intended to relate directly to concerns prevalent in the Global South. It stresses “host-state consent” – that any security cooperation or external involvement must have the approval of the country concerned – while opposing unilateral sanctions and bloc confrontation, positioning China as a counterweight to West-led security frameworks.

Contrasts with the West: “The so-called rules-based order is just a cover for western hegemony and double standards”

China leverages ongoing global tensions to contrast its engagement with that of the West, directing accusations of what it sees as western, primarily US, double standards, hegemonic behaviour and coercion. Events like the war in Gaza, and the wider plight of Palestinians, evoke memories of colonialism and foreign domination for many in the Global South and are used to strengthen a narrative that positions China as a credible alternative and moral counterpoint to the West. In this framing, the failings of western-led global governance are used to reinforce China’s call for a more just international order – one in which it claims a leading role. Together, these messages serve a dual purpose: enhancing China’s discourse power by cultivating its appeal in the Global South while undermining the West’s narrative authority. This dynamic sits at the heart of China’s push for discourse power.

In its outreach to the Global South, China is not just seeking economic or strategic partnerships – it is advancing a competing vision of global order. Its messages of solidarity, common development and “true multilateralism” all serve a broader objective: to gain support for the reconfiguration of global norms and institutions in line with the CCP’s interests. It also reflects China’s long-term effort to reshape global norms and highlights the historical continuity in its ideological framing of relations with the Global South.

China’s approach often blends material incentives with ideological alignment – offering infrastructure and trade, while also seeming to affirm the sovereignty, dignity and distinct path of developing countries. Whether this messaging is accepted uniformly, however, is open to question; there is scepticism, especially in the light of local concerns over debt and growing scrutiny of BRI projects.

Nonetheless, China’s strategic narratives might be finding greater resonance across the Global South. Western leadership is increasingly fractured – exacerbated by Donald Trump’s return to the White House and the US retreat from global engagement, notably the shutdown of USAID. Meanwhile, a recent survey by the Alliance of Democracies Foundation shows that, for the first time, global perceptions of the US have fallen below those of China, whose favourability has risen since last year. With this shift in global perceptions, China’s efforts to present itself as a stable and reliable partner carry new weight.

Om författaren

One year in: What Trump means for China